Understanding your obligations as a vehicle owner in China is crucial, especially regarding vehicle license fees. This framework includes various annual costs that every driver must consider, from vehicle and vessel use taxes to insurance. As we explore each aspect, specific chapters will shed light on the structure of these fees, nuances for new energy vehicles, regional variations, economic impacts, and regulations. Together, they paint a picture of the financial landscape surrounding vehicle ownership in China, ensuring readers are well-informed and prepared.

Cracking the Vehicle License Fee: A Roadmap Through China’s Plate Policies, Taxes, and Ongoing Costs

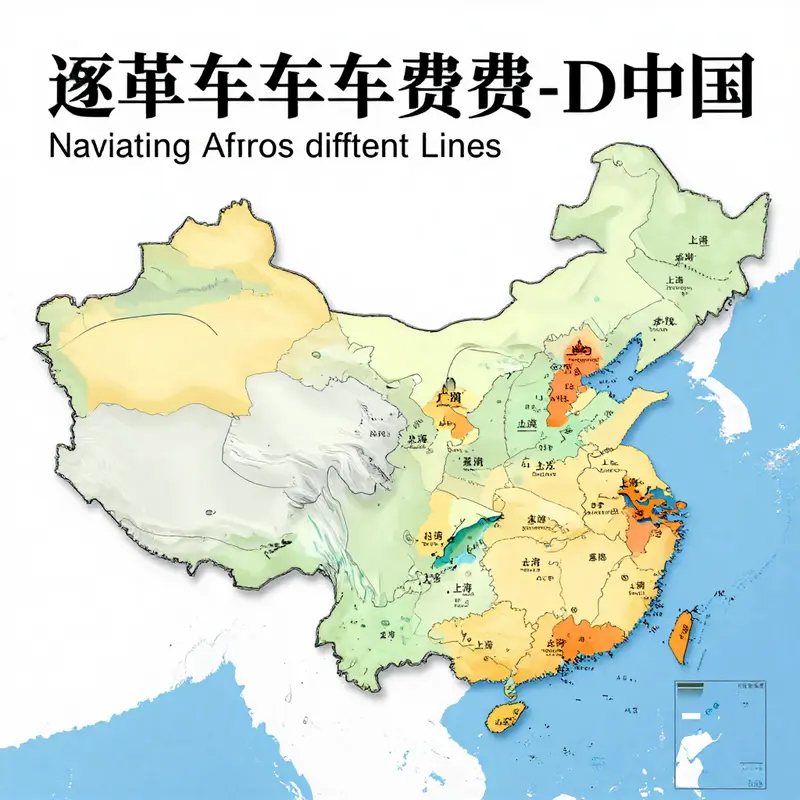

Owning a car in China comes with a cost story that unfolds year after year, well beyond the sticker price. The so‑called vehicle license fee is not a single fixed sum; it is a bundle of mandatory charges and taxes tied to registration, use, and the evolving rules of place and policy. To understand what a vehicle will cost to operate, it helps to follow the thread from the moment a car is first registered through each year of cruising on city streets and winding highway ramps. The most recognizable piece is the annual Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, a levy that scales with engine displacement and vehicle type, but local governments in practice add their own rhythms to the rate schedule. For a sense of the landscape, many provinces apply bands that place small, efficient cars in the lower end and larger, higher‑powered vehicles in the upper bands. Typical ranges exist, such as 60–360 RMB per year for engines of 1.0 liters or less, 300–540 RMB for 1.0–1.6 liters, 360–660 RMB for 1.6–2.0 liters, 660–1,200 RMB for 2.0–2.5 liters, 2,400–3,600 RMB for 3.0–4.0 liters, and 3,600–5,400 RMB for engines over 4.0 liters. It is important to note these numbers vary by region; major metropolitan zones like Beijing and Shanghai generally push higher than more commerce‑driven provinces such as Guangdong. This regional nuance matters because it reframes the cost picture for a family buying in one city versus another, even when the car itself is the same model and specification.

Adjacent to the annual tax is the annual inspection fee, a routine check that typically covers basic emissions and appearance requirements. In practical terms, most local authorities charge roughly 100 to 300 RMB for this check; older vehicles or special situations such as cross‑provincial transfers can incur additional charges. This inspection cycle acts as a steady reminder that a vehicle’s operating state—its emissions footprint, its safety features, its roadworthiness—remains under ongoing scrutiny. Alongside these standard fees sits the compulsory traffic insurance, legally required for all vehicles. Known as CTPLI or third‑party liability insurance, the premium is designed to reflect the vehicle’s use and risk, with a broad annual range approaching 900 to 1,500 RMB depending on vehicle category and driving history. Though not a license fee in name, CTPLI is a prerequisite to obtaining or renewing a license plate, and its certainty contributes to the overall cost of keeping a car on the road.

Beyond these fixed annual charges, the price of fuel quietly shifts the ongoing cost of motoring. Since 2009, fuel tax has been integrated into the price of gasoline and diesel, so your per‑liter cost already includes a levy intended to support road maintenance and infrastructure. In rough terms, expect about 1 RMB per liter for petrol and approximately 0.8 RMB per liter for diesel; this tax is invisible at the pump as a separate line item, but it remains part of the price you pay each time the tank is filled. Parking fees and highway tolls introduce more variability, changing with location and the patterns of usage. A resident in a dense urban center may face higher on‑street or garage parking costs, while highway tolls accumulate with longer trips or routes that bypass alternative roads. Taken together, these elements compound the recurring annual cost picture, adding a practical discipline to budgeting for car ownership.

A newer and increasingly salient element of the license‑fee landscape concerns New Energy Vehicles (NEVs). Starting in 2025, NEVs that rely on electric propulsion or alternative powertrains must endure a battery inspection fee of 300 RMB. This additional line item is intended to bolster safety oversight specific to battery systems and does not apply to conventional internal‑combustion vehicles. The NEV story, however, does not end with this inspection fee. In many cities, NEVs continue to benefit from subsidies or favourable treatment in other tax and registration policies, including exemptions or reductions in purchase tax in certain locales. While the battery check adds a clearly defined cost, the wider NEV framework still positions these vehicles as economically distinct from traditional gasoline or diesel models, particularly when city rules encourage or reward their adoption through incentives that reduce other upfront or annual costs.

Purchasing or transferring a vehicle introduces a separate set of fees that can tilt the decision to buy, sell, or swap a car. The Vehicle Purchase Tax amounts to 10 percent of the pre‑tax price, calculated in a specific way that typically involves the listed price before tax and a conversion factor used by the tax authorities. The practical effect is that the tax is not simply a flat 10 percent of the price you see advertised; it is a calculated share that can influence the overall cost of acquisition. In addition, registration and documentation fees apply at the point of sale or transfer. A license plate carries a flat charge, around 100 RMB in many places, while the registration certificate carries a smaller fee, about 15 RMB. Some cities have either abolished or reduced the traditional chop stamping fee, a relic of the paperwork process that previously accompanied registration. These one‑off charges, while not large in isolation, accumulate when a vehicle changes hands or when multiple vehicles pass through a household during a year of activity.

When a vehicle changes ownership, a transaction tax comes into play as well. Private sales typically incur a 1 percent tax on the vehicle’s assessed value, while corporate transactions are assessed at 3 percent. For luxury vehicles—those priced well above a certain threshold—an exemption from consumption tax can apply in some cases, creating a further layer of complexity in evaluating the true cost of a high‑end purchase. Taken together, these transfer costs can be decisive in a buyer’s overall budget, especially for second‑hand markets where demand and valuation shift rapidly with regional demand and policy nuance.

The overall structure, then, is not a single line item but a tapestry woven from regional rates, vehicle type, usage, and lifecycle events. The most visible lines—the annual tax, the inspection, and the mandatory insurance—settle into a predictable cadence year after year, while the fuel price moved by global markets, urban parking pressures, and toll networks add a dynamic edge to every commute. The NEV path introduces both a fresh cost (the battery inspection) and a potential for offsetting subsidies that can tilt a regional calculus in favor of electric or hybrid choices. Meanwhile, the purchase and transfer costs remind buyers that the journey does not end at the moment of signing the registration papers; it continues through ownership, resale, and, in some cities, even the method by which new registrations are allocated, such as lotteries or auctions for scarce plates.

For readers seeking broader context, a useful touchstone is how regional rules shape the wider licensing landscape. Different provinces and municipalities maintain distinct approaches to licensing and road use, and this is precisely why the numbers you see in one city may not mirror those in another. The interplay between plate allocation policies, local tax rates, and insurance premiums means the true annual cost can vary by a wide margin even for identical vehicle specs. To explore how regional policy can influence driver licensing more generally, consider the discussion on state rules impact on driver licensing.

In practice, the most responsible way to anticipate the total cost of vehicle ownership in China is to consult the relevant local authorities—typically the Car Administration Office or its regional equivalents—and to review official guidance from the State Taxation Administration. This approach ensures that a prospective buyer or new owner understands both the baseline charges that apply nationwide and the regional adjustments that may affect the annual budget. The official channel for the tax treatment of vehicle purchases remains a critical reference: the policy released by national tax authorities clarifies how purchase tax is calculated and how exemptions or adjustments may be applied over time.

As a practical takeaway, framing the license fee as a portfolio of recurring costs plus periodic one‑offs helps buyers and owners model cash flow across ownership. It also makes clear why some cities, despite high upfront plate prices or registration hurdles, can become comparatively affordable environments for ongoing ownership due to favorable tax treatment, lower tolls, or more manageable parking costs. For the reader who wants a tangible starting point, budgeting should begin with the annual vehicle tax and the compulsory insurance as fixed anchors, then layer in the fuel costs based on expected mileage, and finally account for the local quirks of NEV incentives, plate policies, or transfer charges. The rhythm of the road, in other words, is learned by reading the local map as you travel the year ahead.

External resource: China’s Traffic Management Department provides official guidance on road‑use policies and enforcement frameworks that underlie many of these charges. For a direct reference to current procedures and regulatory updates, visit https://jtt.mps.gov.cn/.

Gates at the Gate: The Vehicle License Fee, New Energy Vehicles, and the Price of Driving

In the broad ledger of owning a car, the vehicle license fee stands as a fixed, recurring line item that quietly but decisively shapes how people value, acquire, and keep their vehicles. It is not a single tax or toll; it is a bundle of mandatory payments and administrative costs that every registered motorist must reckon with each year. The core components—Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, the annual inspection, compulsory traffic insurance, and the fuel tax embedded in fuel prices—form a baseline cost that every owner cannot escape. Yet the landscape shifts when new energy vehicles (NEVs) enter the equation, not simply because NEVs may use electricity instead of gasoline, but because policy design uses licensing costs as a critical lever to steer consumer choice, urban planning, and the pace of the transition to cleaner mobility. In this sense, the vehicle license fee becomes a hinge: it can either lower barriers to NEVs through preferential plate policies and targeted exemptions, or raise the cost of ownership in ways that dampen enthusiasm for electric models. The result is a nuanced, regionally variegated reality in which the cheapest path to car ownership for one buyer may be very different from another’s, depending on where they live, what kind of vehicle they choose, and how policymakers balance revenue needs with climate and congestion goals.

To understand the NEV-specific dynamics, it helps to map out the incremental costs that accumulate alongside the base license fee. The Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, a yearly levy tied to engine displacement and vehicle type, historically punishes large, high-displacement engines with higher bills, while rewarding lighter, more efficient configurations. In practice, the annual cost climbs quickly as engine size increases—from modest sums for small city cars to thousands of renminbi for higher-performance, larger vehicles. This tax is not uniform; it varies by region, with metropolitan hubs like Beijing and Shanghai typically demanding higher payments than other provinces such as Guangdong. The geographic spread of these costs matters because it interacts with NEV promotion in different ways across cities that wield license plate quotas more aggressively. The annual inspection fee, a routine check focused on emissions and safety, adds another persistent cost layer, with additional charges possible for older vehicles or for cross-provincial transfers. Then there is compulsory traffic insurance, a mandatory but variable expense that reflects vehicle type and the driver’s history, typically in the hundreds to low thousands of renminbi annually. And while many think of fuel tax as a separate expenditure, in China fuel tax has been integrated into fuel prices since 2009, so the cost is embedded at the pump—about 1 renminbi per liter for petrol and roughly 0.8 renminbi per liter for diesel. Even when the vehicle itself is electric, ownership involves costs connected to charging habits, maintenance, and network access, which can indirectly influence perceptions of value and total cost of ownership.

The story grows more intricate when NEVs enter the frame. Starting in 2025, a dedicated NEV battery inspection fee of 300 renminbi was introduced to bolster safety standards, a cost that conventional vehicles do not incur. While this fee adds to the first-year ownership cost of NEVs, the big policy lever remains the license plate regime. In many Chinese cities, license plates are allocated through quotas, with lottery draws or auctions determining who gets to buy a car in a given period. In dense urban centers—Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou in particular—the barrier to obtaining a plate can be formidable and costly, creating a powerful incentive to choose a NEV that receives preferential treatment under the plate policy. Several cities have responded by offering free or discounted license plates for NEVs, a direct and tangible reduction in the total ownership cost for electric vehicles. This targeted approach—coupled with the inherent lower operating costs of NEVs, such as cheaper electricity per kilometer and fewer moving parts—helps NEVs edge ahead in the mass market, especially among urban residents who face tight parking and congestion constraints.

Scholars have pointed to plate control and preferential NEV policies as critical drivers of NEV adoption in the country. In particular, there is evidence that when plate access is regulated tightly, reducing the price and improving the availability of NEV plates, demand for electric models rises. The logic is straightforward: if the cost of securing a license plate for a conventional vehicle becomes prohibitive, the relative attractiveness of NEVs increases, particularly when the policy environment offers additional carrot-and-stick incentives. This dynamic does not operate in a vacuum. It is nested within regional tax regimes, purchase tax adjustments, and evolving standards for NEV tech—standards that influence which models qualify for reduced fees or expedited registration—creating a multi-layered incentive architecture that can either accelerate or slow the transition to cleaner mobility.

Policy evolution continues to reshape the economics of NEV ownership. Beginning in 2026, new electric private cars in China will face a revised fee structure upon registration, signaling a shift toward sustainable funding models for infrastructure while introducing a potential new cost for earliest adopters. The policy also introduces a four-year grace period for existing vehicles before renewal fees apply, a transitional measure designed to ease the shock for current owners who might otherwise face immediate financial strain when the new framework takes effect. In parallel, the 2026–2027 policy bundle includes a significant incentive: a half-rate reduction in the vehicle purchase tax for NEVs, capped at 15,000 yuan in savings. This combination of a lower purchase tax, a transitional grace period for existing vehicles, and enhanced technical standards is designed to tilt the economics in favor of NEVs while ensuring that the funding needs of the road network are met over time.

An important part of the NEV policy architecture is the standard-setting around technical performance. The upgrade in NEV requirements—such as raising the minimum pure electric range for plug-in hybrids from about 43 kilometers to at least 100 kilometers—ensures that models qualifying for the favorable tax and licensing treatment are genuinely capable of delivering extended electric operation. In other words, the policy aims to prevent short-range, low-value electric models from exploiting tax breaks while not contributing meaningfully to emissions reductions. The effect is twofold: it protects the integrity of the incentive system and nudges consumers toward vehicles whose real-world performance aligns with a broader strategy to reduce urban pollution and oil dependence. For buyers, these standards translate into a more predictable and measurable set of expectations when they evaluate NEVs against conventional cars, especially in metropolitan areas where the license plate game is most intense.

The broader lesson is that the vehicle license fee, while seemingly a straightforward cost, functions as a strategic instrument within a larger policy toolkit. When designed to favor NEVs through plate access or direct subsidies, it lowers the perceived and actual cost of ownership for electric models. Conversely, if license-related charges rise without compensating benefits, the financial appeal of NEVs can waver, particularly for buyers weighing the long-term costs of ownership in a city with high plate competition. The balance policymakers seek is delicate: secure a robust funding base for road maintenance and infrastructure while lowering the incremental cost of NEVs enough to overcome the higher upfront price and the often imperfect charging ecosystem in some regions.

This balancing act has real consequences for consumers and for the pace of electrification. In places where the license plate regime remains a primary barrier to new registrations, NEV buyers may flock to models that offer plate advantages, even if those models are not the top performers in other dimensions. In contrast, where plate policy is more open to NEVs and when the purchase tax and registration costs are softened, households face a lower barrier to entry, and the choice landscape tilts more decisively toward electrification. The same logic applies to the total cost of ownership. A comprehensive calculation includes the base license tax, annual inspections, insurance, fuel or electricity, charging infrastructure costs, and the evolving regulatory environment surrounding NEVs. A buyer who factors in a four-year grace period and a half-rate purchase tax can see a meaningful difference in the net present value of owning an NEV versus a conventional vehicle, particularly for urban commuters who accumulate a high number of annual kilometers and face expensive license plate access.

The dialogue around NEVs and the vehicle license fee also invites comparisons beyond China. For instance, in the United States, policy shifts linked to road funding can dramatically alter registration fees and, by extension, ownership costs across states. A notable case is Michigan, where a late-2025 road funding deal sparked a sharp rise in annual vehicle registration fees, making Michigan’s fees among the highest in the nation by 2026. The outcome is not a blanket verdict on EVs; even as ownership costs rise in some contexts, other incentives—such as parking benefits or reserved lanes for EVs—can counterbalance higher fees and sustain demand. The broader narrative underscores a central insight: policy design matters. If fee structures evolve in ways that reward cleaner technologies and reduce the relative cost of NEVs, adoption accelerates. If they add friction without offsetting incentives, demand may stall, even for technically superior or more affordable electric models.

For consumers navigating these shifting currents, the practical takeaway is clear. When evaluating the economics of NEVs versus conventional vehicles, count not only the sticker price but also the annualized license costs, inspection fees, insurance, and the possible plate advantages that can dramatically alter the payoff calculus. Region matters a great deal; cities with generous NEV plate policies and favorable tax treatment can turn the lifetime cost of an NEV into a compelling bargain, while others with stricter control and higher regional taxes can dampen enthusiasm. The policy landscape will continue to evolve as governments seek to fund road networks and incentivize cleaner fleets, and buyers who stay informed about these changes—especially the upcoming 2026 changes in fee structure and the scope of tax reductions—will be better positioned to optimize their purchase decisions over the life of the vehicle. The next step in this exploration turns toward how drivers, insurers, and municipal planners respond to these incentives in practice, and how this responsiveness feeds back into policy design and the broader trajectory of motorized transport.

Internal link reference: state rules and driver licensing play a role in how these policies are implemented at the local level, which can alter the practical costs and accessibility of NEVs as part of daily life. See the discussion here: state rules impact on driver licensing.

External resource: Michigan EV fees spike under road funding deal, now. https://www.mlive.com/news/michigan/2026/01/michigan-ev-fee-spike-under-road-funding-deal-now.html

Beyond the Sticker: How Vehicle License Fees Shape Ownership, Mobility, and Economic Life

Understanding the vehicle license fee goes beyond tallying a line item on a quarterly budget. It sits at the intersection of public finance, urban planning, and everyday decision making. In its core, the annual license charge bundles fixed, recurring payments—such as the Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, annual inspections, compulsory traffic insurance, and fuel-related levies—that together influence how households assess ownership, how cities finance roads and safety programs, and how the broader economy allocates resources. The exact amounts vary by region and vehicle type; higher urban densities and stricter environmental targets usually translate into higher brackets, while new-energy vehicles may receive relief in other charges though they incur specific safety costs. Beyond the fixed costs, location and driving patterns shape parking charges and tolls, which further influence choices toward efficiency, public transit, or shared mobility. Framed this way, vehicle license fees become a policy instrument that balances individual mobility with public finance needs and environmental goals, rather than a simple budgeting line item.

A Patchwork of Fees: Navigating Regional Vehicle License Costs Across China

The cost of owning and using a motor vehicle in China extends far beyond the purchase price. A complex tapestry of regional policies and national frameworks creates a layered landscape of fees that change with where you live, what you drive, and how you move your car through the country’s dense urban networks. This patchwork matters not only for the monthly budget of individual owners but also for public policy aims around congestion, air quality, and the transition to cleaner mobility. When readers imagine the true expense of ownership, they must look past the sticker price and into the recurring charges that accompany registration, operation, and transfer of vehicles. In practice, the vehicle license fee system weaves together mandatory taxes, inspections, insurance, fuel costs, and occasional region-specific charges, producing a total annual burden that can differ markedly from one city to the next and from one province to another. regional variation is not a quirk; it is deliberate policy designed to steer behavior in crowded cities and to align local revenue needs with the broader national goals for transport and environmental management.

At the core of the annual cost is the Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, widely referred to as the car tax. This is the year-by-year price tag attached to owning a car, and it is calibrated by engine displacement, vehicle type, seating capacity, and whether the vehicle is privately or commercially used. The numbers matter, but so does geography. For example, the tax bands show a clear progression: smaller engines may incur two-digit to low-three-digit annual figures, while larger, high-displacement vehicles climb into the hundreds or thousands of RMB per year. Within this structure, regional authorities set the precise rates within nationwide guidelines, so a 1.0 liter car in Shanghai can cost more to tax annually than an identically configured car in Guangdong. These regional adjustments reflect differences in urban form, environmental goals, and the local fiscal framework, reinforcing the essential point that price signals in China’s car market are not uniform across the country.

Beyond the car tax, a series of annual charges keeps the vehicle legally usable. The annual inspection fee focuses on emissions, safety, and appearance checks. Basic inspections typically fall in the 100 to 300 RMB range, with older vehicles or cross-provincial transfers sometimes multiplying the cost. The CTB, or compulsory traffic insurance, is another non-negotiable annual expense. The cost of this mandatory insurance mirrors vehicle risk profiles and driving history, typically landing somewhere in the 900 to 1,500 RMB band, though variations exist depending on the vehicle class and the driver’s record. Taken together, these two items—the annual inspection and CTP—constitute a predictable core of the annual cost, even as other charges may shift with location.

Fuel taxes, which have been embedded in the price of gasoline and diesel since 2009, further shape the long-run cost of vehicle operation. Rather than a separate, visible levy on each fill-up, fuel tax is built into the pump price, with approximate per-liter increments like 1 RMB for petrol and around 0.8 RMB for diesel in many regions. The practical effect is that fuel consumption increases or decreases a household’s annual vehicle outlay, with the regional price environment playing a significant role as well. Parking fees and highway tolls, variable by city and route, add a further layer of cost that can swing markedly with driving patterns. In dense metropolitan corridors, the burden from parking and tolls can rival or exceed some fixed annual fees, depending on how often a car is used to navigate congested cores or long intercity trips.

New energy vehicles (NEVs) introduce a more recent wrinkle in the regional pricing map. In 2025, a battery inspection fee of 300 RMB was introduced to NEVs, intended to safeguard safety in the charging ecosystem and battery management. This charge does not apply to conventional internal-combustion vehicles, which means the comparative economics of NEVs versus traditional cars shift not just in purchase subsidies or range, but in the annual cost ledger as well. The NEV battery inspection fee contributes to the broader policy aim of ensuring safety and reliability in an era of rapid electrification, while remaining a regional instrument rather than a universal surcharge.

When purchases or transfers occur, several additional charges come into play. The Vehicle Purchase Tax, calculated as 10% of the pre-tax price through a standard formula, remains a major upfront consideration. Registration and documentation fees are comparatively modest—around 100 RMB for the license plate and 15 RMB for the registration certificate—yet some cities have dissolved other small fees, such as chop-stamping, to streamline processes. For transactions, a 1% transaction tax applies to private sales and 3% for corporate deals, with possible luxury exemptions for vehicles above certain price thresholds. On this front, regional discretion again matters: some locales adjust or reinterpret the base rules to align with tax collection goals or local market conditions.

The central government does set baseline standards, but regional governments wield substantial autonomy in implementing the licensing ecosystem. This is where regional variation becomes most pronounced. Shanghai, in particular, has developed a differentiated license plate pricing mechanism designed to manage intense demand and congestion. A 2023 study by a noted researcher showed that the price of securing a license plate in Shanghai could represent a meaningful share of a vehicle’s overall cost—roughly 13% of the car’s purchase price in that market. The implication is clear: in cities with scarce plates, the financial gateway to ownership is higher, and the cost of waiting—both in time and money—adds another dimension to the affordability question. This differential pricing aligns with broader policy ambitions to steer buyers toward cleaner or smaller options, including electric vehicles, and to dampen the pressure on crowded urban arteries.

The contrast with other regions is equally instructive. In many places, the licensing landscape remains comparatively straightforward or less expensive, with the base costs for registration and plate issuance modest and the annual charges less dramatic. The nationwide baseline for the driver’s license itself—distinct from the license plate—is taxed via a standard 10 yuan fee per license, while additional examination or administrative fees apply. Provinces and municipalities frequently layer on their own supplemental charges and procedures. The result is a broad spectrum of outright costs, administrative complexity, and procedural variance that can be daunting for a new car owner or a consumer considering a move between regions. The central message across these experiences is that region-specific policy choices shape the financial burden of ownership as much as the vehicle’s technical specifications do.

In this regional maze, comparisons often highlight how government incentives and penalties interact with the practical realities of daily mobility. Hong Kong, while not on the mainland’s plate-price spectrum, offers subtle contrasts through environment-friendly incentives for commercial vehicles, illustrating how neighboring governance structures can indirectly influence total ownership costs by altering the economic calculus around certain vehicle types. The broader lesson for potential buyers is that where you register, where you drive, and how often you require parking or toll access can alter the annual price tag in ways a simple purchase price cannot capture.

For individuals planning to drive in China with foreign licenses, the licensing journey is also embedded within this cost ecosystem. Applicants must prepare a set of standard documents, including identification, medical attestations, and translations if necessary. The process, while routine in the sense of bureaucratic steps, adds further administrative overhead and can influence the timing of when a vehicle actually enters service. The friction of licensing—time, paperwork, and regional peculiarities—relates to the broader theme of regional policy as a driver of total cost of ownership. As a result, readers should not view licensing as a single, uniform hurdle but as a dynamic phase that interacts with regional rules, plate scarcity, and local registration practices.

Given the fluid and evolving nature of these policies, the most reliable path for current costs is a direct check with the local motor vehicle administration office and the official government platforms. The landscape changes with traffic conditions, urban development plans, and environmental targets, so staying informed about the latest regional adjustments is essential to avoid surprises. In practice, those weighing whether to purchase a new or used vehicle, or relocate to a different city, should estimate the annual car tax, inspection, insurance, fuel, and parking costs for the specific locale and compare them to their expected driving patterns. This approach yields a grounded sense of affordability that transcends the headline purchase price.

For readers seeking to connect these details to broader policy considerations, the evolving literature on differential plate pricing and EV adoption in a major urban center provides a rigorous backdrop. See the external resource for deeper analysis of how pricing signals interact with technology choices in a major urban center: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0957178823000654. On the internal side, policy readers can explore how regional rules shape licensing experiences through the lens of local governance and driver licensing practices in different provinces by examining the dynamics at the state level: https://drivernvehiclelicensing.com/state-rules-impact-on-driver-licensing/. This combination of regional insight and policy analysis helps illuminate why the total cost of vehicle ownership in China remains a moving target, shifting with the calendar, the city, and the vehicle’s own evolving profile of efficiency and safety requirements.

Decoding Vehicle License Fees: How Governments Fund Roads, Regulation, and the True Cost of Owning a Vehicle

The phrase vehicle license fee often lands as a single line on a receipt, but the charge represents a web of public policy designed to fund roads, regulate safety, and manage the burden of vehicle use on communities. When you own a motor vehicle, the annual fixed costs go beyond the sticker price and the monthly fuel bill. They reflect a constellation of mandatory payments that governments impose to keep infrastructure viable, ensure compliance, and preserve safety on crowded streets. In the Chinese context, these costs unfold through several distinct, mandatory payments that recur year after year, each with its own logic and range. The Vehicle and Vessel Use Tax, commonly referred to as the car tax, is calculated according to engine displacement, vehicle type, seating capacity, and usage—private or commercial. The numbers vary widely by region and vehicle size: a 1.0 liter engine or smaller can incur 60 to 360 yuan per year, while a car in the 3.0 to 4.0 liter bracket might face 2,400 to 3,600 yuan, and engines over 4.0 liters can reach 3,600 to 5,400 yuan annually. These brackets are not universal; they shift from Beijing to Shanghai and even between Guangdong’s more modest traffic zones. The car tax is not merely a fee to own a car; it is a mechanism aligned with environmental considerations, road wear, and urban planning priorities. Alongside the tax, there is the annual inspection fee, a straightforward but essential check on emissions and appearance. Basic inspections typically fall within a lightweight band—roughly 100 to 300 yuan—yet older vehicles or cross-provincial transfers can invite higher costs or additional checks. The aim is to ensure a vehicle remains compliant with emissions standards and roadworthiness, reducing the risk to drivers and the public. Then there is the Compulsory Traffic Insurance, known in many places as CTI or a similar compulsory policy. This insurance is mandatory for all vehicles and its annual cost fluctuates with vehicle type and driving history, commonly landing in a range around 900 to 1,500 yuan. It is not simply a protective shield for the vehicle owner; it is a social measure to provide a predictable baseline of liability coverage in the event of accidents, injuries, or damage on the road. The funding architecture also interleaves with fuel pricing. Since 2009, fuel tax has been integrated into the price of gasoline and diesel, replacing some road maintenance charges with a tax embedded in every liter purchased. The effect is twofold: it broadens the tax base to reflect distance and fuel use, and it creates a direct link between driving behavior and government revenue. In practice, this means that the user pays more when they burn more fuel, aligning cost with usage and environmental impact. Parking fees and highway tolls introduce additional, location-specific costs that can vary by city and route. The institutional design here is simple in principle but variable in practice. Tolls depend on the highway, the type of vehicle, and the distance traveled; parking charges depend on municipal policies and the timing of the stay. Shifting policy priorities can also introduce new costs at the margins, especially as cities experiment with congestion pricing, permit zones, or time-based rates that influence when and where drivers can use certain roads. A notable new element emerging in the policy landscape is the New Energy Vehicle, or NEV, category. Beginning in 2025, NEVs face a 300 yuan battery inspection fee to ensure safety in battery systems and overall vehicle integration. This fee targets the unique safety considerations of high-voltage packs and battery management systems, distinguishing NEVs from conventional internal-combustion vehicles. The fee is modest in isolation, but it is a reminder that the regulatory framework evolves with technology. When a vehicle is bought or transferred, several ancillary costs arise. The Vehicle Purchase Tax, a standard element in many markets, is calculated at 10% of the pre-tax price. The method of calculation can appear arcane at first glance, but it translates to a purchase price divided by 1.17, then multiplied by 10%. This approach ensures a consistent tax base across different price points and helps avoid under- or over-collection due to tax-inclusion quirks. Registration and documentation costs add another layer: typically, 100 yuan for a license plate and 15 yuan for the registration certificate. Some cities have done away with smaller “chop stamping” fees, reflecting a broader government drive toward simplifying procedures and reducing the friction of ownership transfer. Private sales can also trigger a transaction tax of 1% of the vehicle’s assessed value, while corporate transactions carry a 3% rate. In some cases, luxury vehicles above a certain threshold qualify for special exemptions, particularly from consumption tax, reflecting policy priorities toward tax fairness or market stimulation. These varied charges underscore a central truth: the cost of vehicle ownership is a composite, not a single price tag. To navigate it well, ownership must be planned with a clear understanding of where the money goes and why. The practical implication is that the license fee ecosystem—and the other recurring costs that accompany vehicle ownership—reflect not only the vehicle’s technical specifications but also the state’s broader priorities: road maintenance, environmental targets, urban mobility strategies, and consumer protection. This is why the same category of charges can look very different across regions and countries, and why a prospective buyer or a current owner must consult the relevant authorities for the most up-to-date information. In China, the State Taxation Administration and local vehicle management offices are the primary sources for the latest policy changes, exemptions, and calculation methods. The official reference, the National Taxation Administration’s Vehicle Purchase Tax Policy, provides the framework for what counts as purchase tax, how it is calculated, and the conditions under which exemptions or adjustments may apply. Staying informed through official channels is essential, because the regulatory environment is not static; changes can alter the tax base, the rates, or the required documentation. The chapter of regulations and practice can appear dense, yet it serves a common purpose: to ensure that the public contributes fairly to the road system while preserving safety and efficiency for all road users. For readers who are tracing the broader logic of licensing and road-use charges, the Queensland example offers a contrasting perspective that helps illuminate how different jurisdictions structure similar goals. In Queensland, the Motor Traffic (Fees) Regulations No. 04 of 2022 set out first-registrations, and they differentiate fees by vehicle category—private cars, commercial vehicles, and electric vehicles among the key groups. The differences acknowledge not only usage patterns but also environmental and safety considerations. Compliance elements are also clear: vehicle owners must keep licenses valid, a mechanism supported by the Vehicle Licence Online Enquiry Platform that allows users to check the validity and expiry of a license. The system nudges owners toward timely renewals and reduces the risk of penalties for lapsed licenses. For buyers, a Certificate of Clearance from the Transport Department is a critical step before completing a purchase. This certificate confirms that there are no outstanding fines or potential suspensions tied to the vehicle, and it is valid for no more than 72 hours from issue, underscoring the urgency of action in the fast-moving real estate of vehicle transactions. Public information requirements further reinforce transparency: all vehicle management stations must display clear information about requirements, fee bases, and service time limits to ensure that the public can navigate licensing services with confidence. The broader intent is to promote fairness, reduce confusion, and support efficient service delivery in a busy regulatory environment. Readers who wish to see the granularity of Queensland’s approach can consult the official document titled Fees & Charges: Fees of Vehicle and Driving Licensing Services, which lays out the schedules and current charges in a formal, accessible format. This cross-cultural comparison helps readers appreciate how the core idea—a recurring, government-imposed cost for vehicle use—takes shape in different legal terrains. It is a reminder that while the numeric values differ, the underlying logic remains consistent: charges tied to ownership, registration, and ongoing use fund infrastructure, regulate safety, and support the state’s broader transport objectives. For those seeking a deeper dive into the specific figures and procedures, the Queensland document provides a concise, regularly updated reference that aligns policy with practice. A direct route to this resource is available, and it serves as a practical companion to the more general considerations discussed here. In practice, successfully navigating vehicle licensing costs requires a disciplined approach to budgeting, a readiness to adapt to policy changes, and an understanding that the price of road use is a public policy instrument as much as a personal expense. As you map out the true cost of ownership, you will see that the license fee is not merely a line item but a reflection of how a society chooses to fund roads, regulate safety, and shape mobility. To explore related discussions on how different jurisdictions frame driver qualification and licensing rules, you can consult further insights such as State Rules Impact on Driver Licensing.

External resource: https://www.transport.qld.gov.au/_data/assets/pdffile/0008/136547/Fees-and-Charges-Vehicle-and-Driving-Licensing-Services.pdf

Final thoughts

In summary, grasping the nuances of vehicle license fees in China is essential for both new and existing drivers. Understanding the structure, regional differences, economic implications, and specific regulations can empower vehicle owners to manage their costs effectively. This comprehensive overview hopefully equips you with the knowledge needed to navigate the complexities of vehicle ownership smoothly.